How bad is eating (red) meat for our health and the environment?

Last Updated : 12 April 2022You may have heard a lot of talk about the health and environmental impacts of meat in recent years. This article outlines the nutritional benefits and risks of eating red and processed meat and describes the environmental impact of these foods. You’ll also discover some useful tips to help you succeed if you are thinking of eating less meat, especially the red and processed types.

What’s the difference between red, white and processed meat?

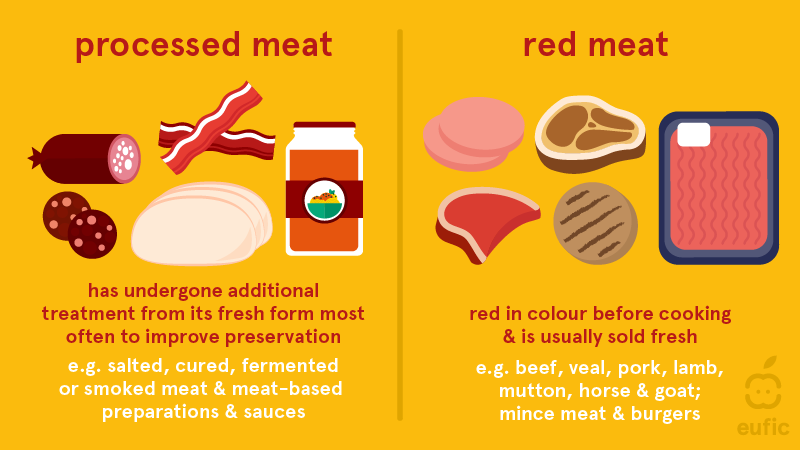

An easy way to distinguish red meat from others is by looking at its colour when it’s raw and fresh. Red meat is red in colour before cooking. It includes different cuts of meat from beef, veal, pork, lamb, mutton, horse, and goat as well as mince and burgers made from these. White meat refers mainly to different kinds of poultry, such as chicken, duck or turkey, as well as other light-coloured meats such as rabbit.

Processed meats are those which have undergone additional treatment from their fresh form, most often to improve preservation. They include salted, cured, fermented or smoked meat products such as bacon, smoked ham and pepperoni, sausages, corned beef, beef jerky as well as canned meat and meat-based preparations and sauces. Processed meats often contain pork or beef but they can also be made from meats that do not come from red meat sources, such as chicken sausages or turkey slices.1

Figure 1 – Difference between processed and red meat.

Is meat bad for your health?

When it comes to the question “is meat bad for you?” – the types and amount of meat we eat, as well as how often we eat it play a key role in the answer. As with any food or specific nutrient, the effects they have on our health can’t be isolated from our overall diet and lifestyle.

Meat in its unprocessed form is a source of high-quality protein and provides many vitamins and minerals in forms that our body can readily digest and absorb which can help easily meet different recommended nutrient targets. Most notably, meat is high in B vitamins, and zinc and particularly red meat is a good source of well absorbed iron (heme iron), vitamin B12 and selenium which are some nutrients that can lack or be in insufficient amounts in unplanned vegetarian or vegan diets. Meat also contains different types and amounts of fat which vary depending on the animal species, age, sex, breed, and feed and the cut of the meat. Fat content in meat is partly responsible for its higher caloric value but on the upside it also makes it a source of fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin A. Red meat is usually higher in saturated fat than poultry2 but removing the visible fat and avoiding adding large amounts of fat (like butter, lard or oils) when cooking can help reduce it.

In 2015, the WHO’s assessment of the carcinogenicity (potential to cause cancer) of red and processed meats stirred the debate on the “healthiness” of these foods. Eating high amounts of red and processed meat was linked to increased risk of bowel cancer, with processed meat having a stronger link than red meat. Such effects are believed to be partly explained by the formation of carcinogenic chemicals in meat after processing (such as curing and smoking) and high-temperature cooking (such as panfrying, grilling or barbecuing).3

While this report provided important insights that reinforce the importance of moderating the consumption particularly of processed meat, the effect of red and processed meat intake on health must be put in the context of the overall diet. There is evidence that other dietary factors such as overweight/obesity and alcohol consumption play a much larger role in increasing risk of different cancers.4 Ultimately, this highlights the need for a varied and balanced overall diet, where the different key food groups are present in the right proportions.

This brings us to an important question: how can we reach the right balance of meat consumption in our diets? In general, dietary patterns that promote a high consumption of fresh, seasonal and local plant-based foods and include only a small intake of meat and dairy products - such as the Mediterranean and the New Nordic diets – have been linked to increased health benefits. Remarkably, the Mediterranean Diet seems to have a protective effect against cancer, cognitive and cardiovascular disease as well as obesity and type 2 diabetes. This diet is based on a high intake of plant foods (such as fruit, vegetables, nuts, cereals and pulses) and olive oil, a moderate intake of fish and poultry and a low intake of dairy products (mainly yoghurt and cheese), red and processed meat and sweets. Similarly, the Nordic Diet, which promotes the regular consumption of local fruits and vegetables (especially berries, cabbages, root vegetables and legumes), native fish (such as herring, mackerel and salmon), legumes, and whole grain cereals (barley, oats and rye) has been linked to lower risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.5 However, those dietary patterns are not the status quo in Europe where meat still tends to be the central source of protein in the diet.

Most European dietary guidelines recommend to limit the amount of red and processed meat in the diet and alternating between different protein sources including fish, poultry/lean meat removed of any visible fat, eggs and plant proteins such as legumes/pulses or tofu. The specific advice on the amount of red meat people should eat regularly varies between countries, with most setting a recommended maximum intake of 500 g of red meat per week. To put it in perspective, two thin slices of ham is around 40-50 g.6

In the case of processed meat (such as charcuteries, sausages and bacon), most countries encourage to eat little, if any but some (such as Poland, Sweden, UK and Norway) give a combined weekly intake limit for both red and processed meat without making distinction between the two.6 Compared to meat in its natural form, processed meats are often high in salt, energy, saturated fats, cholesterol and other compounds formed during processing, which can harm health if eaten in excess. You can find out more about your national dietary guidelines here.

Is red meat bad for the environment?

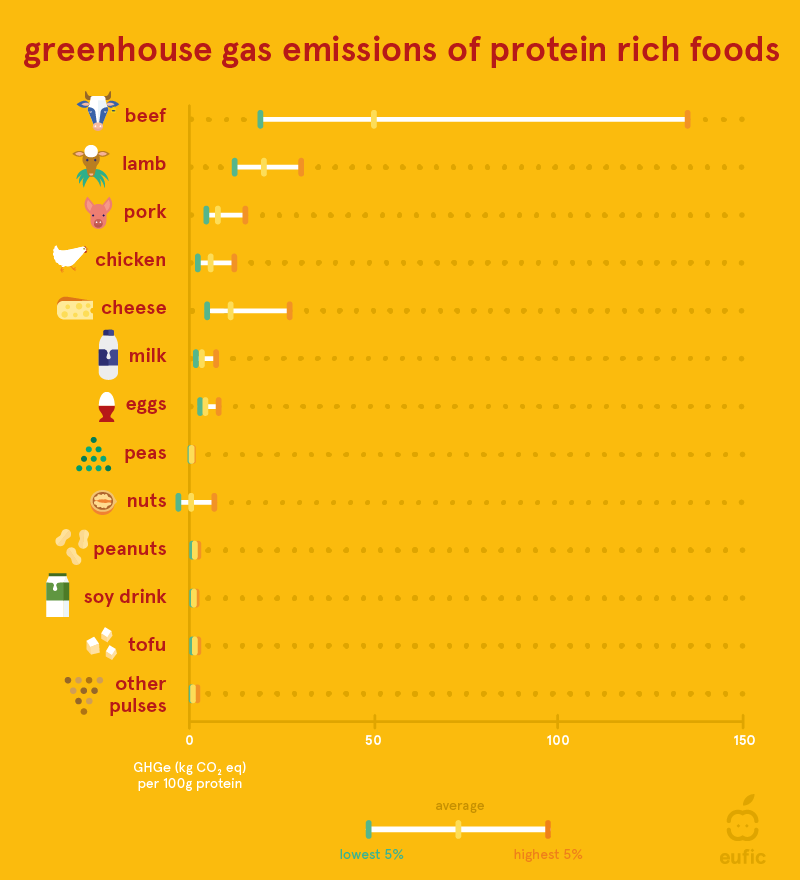

Animal products, and particularly the rearing of livestock for meat, eggs and milk, are an important part of the environmental equation, especially when it comes to land use and greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions. The emissions are significantly larger for ruminant meats, such as beef and lamb which can produce up to 250 times more GHG per gram of protein than legumes. Other animal proteins, such as eggs, dairy, poultry and pork have much lower emissions per gram of protein than ruminant meats even if they’re higher than those of plant foods like cereals and pulses.7

Figure 2. Greenhouse gas emissions of protein rich foods.8 Lowest 5% describes that 5% of production systems for that particular food emit that amount or less. Highest 5% means the top 5% of production systems for that particular food emit that amount or more.

Land use and degradation is also a point of concern when it comes to meat and dairy, since livestock uses about 70% of agricultural land, including a third of arable land, also needed for crop production. Grazing livestock, and less directly, the production of feed crops are the main agricultural drivers of deforestation, biodiversity loss and land degradation.9

At the same time, the impacts of climatic and environmental change are already starting to make food production more difficult and unpredictable in many regions of the world. There is a need for dietary changes that can help relieve the environmental burden of food production as well as improve human health worldwide.10

The 2019 EAT-Lancet report on “healthy and sustainable diet” set for the first-time scientific targets for healthy diets and sustainable food production that could help protect the planetary boundaries Shifting to these diets would need a larger than 50% reduction in global consumption of some foods, such as red meat (mainly by reducing excessive consumption in wealthier countries) and sugars; and more than doubling the intake of whole plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts.11

These conclusions are supported by a large body of evidence on the environmental impacts of different diets, where general consensus is that diets with more plant-based foods and with fewer animal foods are a “win-win” for both the health of people and the planet.12

How to start eating less meat?

If want to strike the right balance between meat and vegetable proteins in your diet, small steps can get you going.

First, define your motivation: why do you want to eat less meat? Being clear about our motives helps us stick to our commitments, so think about whether it’s related to health, the environment, animal welfare or even just a means to vary your diet.

Secondly, make a plan. When it comes to setting new habits, improvising won’t work and it’s helpful to have a plan in place that prevents you from having to decide in the moment. For example, if you decide to start having meatless Mondays for a month, one way to prepare for it is to create a list with different recipes beforehand and ensure have all the ingredients needed on Sundays.

Start small and realistic. Breaking down big goals into small objectives that can be sustained over time, is key to ensure consistency which is the main factor in changing your eating habits. If you eat meat every day, it might be a bit too ambitious and overwhelming to try and cut out meat entirely for a month. But if you start by aiming to have one meat-free meal once a week for a month, you’ll have a much higher chance of success and feel confident to progress to a few meat-free meals a week in the following months.

Lastly, choose changes that are simple, pleasurable and convenient for you. If you work late hours and often rely on take-away food for dinner, one simple way to start can be trying vegetarian options from the menu, instead of deciding to cook a vegetarian meal from scratch.

Most importantly, our diets are personal, and our choices depend on different factors, such as our budget, time and taste preferences. When it comes to doing our part in cutting down meat, there’s no one-size-fits-all and different strategies will work best for different people. The key to success is finding the ones that you can stick to effortlessly and with joy – so let’s get started!

Tips to eat less (red) meat

- Avoid processed meat and make red meat less than a quarter of the meat you eat.

One of the core pillars of a healthy and balanced diet is variety, which also applies to protein sources. Therefore, this can be a simple strategy to moderate your intake of red meat and meat in general. Simply put, red meat should make up no more than one in four of the times you eat meat.13 By varying your sources of protein to include more pulses, meat substitutes, sustainably sourced fish and eggs you will not only reduce your meat intake but also expand the range of nutrients you get from your diet.

- Pay attention to portion sizes

As a rule of thumb, a portion of meat should be about the size of the palm of your hand. If you’re exceeding this recommendation, adjusting your portions sizes will directly help you reduce your meat intake.

- Swap half of the meat content in dishes or your plate with vegetable proteins such as pulses (beans, lentils, chickpeas, etc.)

Meals don’t have to be completely meat-free to make a difference. Replacing half of the meat in your recipe/plate by a plant-based protein will help you reduce your meat intake while helping you become more familiar with these sources. A good example is replacing 50% of the minced meat with lentils when preparing Bolognese sauce. Look for recipes to see what are the best substitutes and combinations for each type of meat and dish.

- Consider blended meat.

Blended meat products are hybrid versions of traditional meat products (such as meatballs, burger patties and sausages) that replace part of the meat with vegetables. One example are burger patties made from a combination of ground beef and pea protein. These products may be helpful if you feel you will miss the classic taste of meat.

- Start by having meat-free meals or days

Challenges like the “meatless Mondays” can be a fun way to start introducing vegetarian meals or days to your routine. One advantage is that these are global movements where you join a large community to find resources, meal inspiration and share also share your experience.

- Learn how to cook tofu, seitan and dry pulses and try the vegetarian versions of your regular meals!

Tofu, seitan and tempeh can be extremely tasty protein rich alternatives to meat if cooked properly. Similarly, you may find you prefer the texture and flavour of dry beans cooked from scratch over that of canned beans. Looking for inspiration and recipes from vegetarian and vegan people or chefs may be the best way to learn the tips and tricks on how to bring out the best flavours and textures of plant-based foods to tasty vegetarian meals. Or check out EUFIC’s guide on cooking plant-based proteins!

- Find convenient alternatives to meat that you like but beware of their nutritional value.

Tofu, seitan and tempeh are the popular kids of the vegetarian proteins, but if you’ve tried them in different ways and you still don’t enjoy their taste or texture, there are still several other protein alternatives. But when looking to buy plant-based products such as burgers, meatballs, etc., always pay attention to labels and check their overall nutritional value. Even if a product contains the vegetarian or vegan symbol, it can still be high in fats and salt. When that’s the case, these products should only be eaten occasionally and as part of a balanced and healthy diet.

References

- The World Health Organization. Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. Questions & Answers. Accessed on 26 Jul 2023

- Lofgren, PA (2005). Meat, Poultry and Meat Products (pp. 230-237). Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition (2nd edition). Academic Press.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group (2015). Carcinogenity of consumption of red meat and processed meat. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective. A Summary of the Third Expert Report 2018.

- WHO (2018). What national and subnational interventions and policies based on Mediterranean and Nordic diets are recommended or implemented in the WHO European Region, and is there evidence of effectiveness in reducing noncommunicable diseases?

- EU Joint Research Centre. Health Promotion & Disease Prevention – Food-based Dietary Guidelines in Europe. Accessed on 26 Jul 2023

- Tilman, D and Clark, M (2014). Global diets link to environmental sustainability and human health. Nature, 515:518–522. DOI:

- Poore J, Nemecek T (2018) Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 360 (6392):987-992.

- Fischer, C and Garnett Tara (2016). Plates, pyramids, planets. Developments in national healthy and sustainable dietary guidelines: a state of play assessment. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and The Food Climate Research Net

- European Commission Communication COM/2020/381 (2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and e

- EAT-Lancet Commission (2019). Healthy Diets From Sustainable Food Systems Food Planet Health. Summary Report of the EAT-Lancet Commission

- Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization (FAO and WHO) (2019). Sustainable healthy diets – Guiding principles.

- Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (2022). Dietary advice for meals. Accessed on 26 Jul 2023.