EUFIC Forum n°6: Sustainability and social awareness labelling

Last Updated : 11 February 2014Research conducted April – June 2012

Key findings

- Most consumers have heard about the term ‘sustainability’, and they relate it predominantly to environmental issues. However, the term is abstract and diffuse and therefore difficult to deal with.

- At the general level, consumers, when asked, express concern about sustainability issues and would like to be informed about them. However, people find it difficult to understand where sustainability can/should influence their food and drink purchases.

- Awareness of sustainability labels varies a good deal between countries, but is generally low. Nevertheless, many consumers can guess the meaning of these labels in a roughly correct manner. The role of sustainability labels in consumer choices is in all likelihood low.

- Compared to issues related to health and nutrition, ‘sustainability’ is more difficult to grasp and therefore also more difficult to make relevant for consumers in their food and drink purchases. In the context of purchase of food and drink, sustainability issues are not (yet) a priority.

- The Fairtrade logo was the most well-known and well-understood in the study; the other labels (Rainforest Alliance, Animal Welfare and Carbon Footprint) were less recognised and understood.

- The results do not necessarily imply that sustainability information will not play a role in future food purchases. This could change when sustainability issues in the context of food and drink become more prominent in the public debate, as it has happened with issues of health and nutrition.

Background

There is growing demand by the public to be informed about the various impacts of food consumption, including effects on the environment, animal welfare and working conditions in developing countries. Information about these issues sometimes appears in the form of labels and logos on the already information over-loaded packaging of food and drinks. Such environmental and ethical labels are distinct from quality labels as they try to encourage individuals to make choices that are beneficial for society (e.g. choices that are environmentally friendly and/or have an ethical dimension).

To date, only a few studies have looked at the broader picture of environmental and ethical labelling. With increasing proliferation on different schemes, formats, and quantification methods available to the consumer, there remain considerable gaps in our knowledge on consumer understanding, perception & attitude, as well as possible effects on purchase and consumption behaviour. Knowledge about sustainability labels on food products and their impact on consumer behaviour is generally limited.

It is important to better understand consumers’ attitudes and behaviour toward environmental and ethical labels due to its potential to enhance a sustainable diet. This research addresses these concerns on a pan-European scale.

Study aims

To explore how consumers in Europe interpret and use sustainability information shown on food and drink labels, addressing the following aspects:

- Meaning and relevance of sustainability

- Familiarity with and understanding of environmental and ethical labels

- If and how sustainability information on packaging influences consumer food choice

- Possible trade-offs between environmental and ethical information against other purchase criteria when buying food

How was the study conducted?

The pan-European study was conducted with panels provided by Ipsos MORI.

For the quantitative part of the study, the representative sample comprised of 4,408 on-line respondents from 6 European countries – UK (602), Germany (811), Spain (661), France (866), Poland (658) and Sweden (810). About half of the participants were men, half women, aged between 18 – 65 years.

Respondents represented a socio-demographic spread across all age groups and education levels. The majority of the sample was comprised of working individuals who were in a full time employment, lived in multiple person households, and did most of the food and grocery shopping.

A pilot study was carried out in the UK in April 2012, followed by the main research from April to June 2012.

The questionnaire consisted of a range of questions on:

- General food and drink buying habits

- Understanding and concern towards sustainability-related topics

- Familiarity and understanding of the sustainability labels Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, Animal Welfare and Carbon Footprint

- Information search behaviour concerning sustainability issues

- Impact of sustainability labels on food choice

- Socio-demographics

The qualitative part of the study included 2 focus group discussions per country, in four countries – Germany, France, UK and Spain. All participants were recruited face-to-face from the local communities. The only criterion for recruitment was that they had to be regular buyers of food and drink products.

In each country, one focus group consisted of people from higher social classes and one was comprised of lower social classes, in order to check for possible differences in their answers.

The discussion guide consisted of questions similar to the survey but was designed to be used flexibly in order to account for specific concerns respondents expressed. Prompts were used at various points to expose participants to sustainability labels (both printed out and on-pack), in order to record their reactions.

Key results

What does sustainability mean to people?

The majority of study participants had a good understanding of the term sustainability. Between 70-90% said they were familiar with the concept – except in Poland where this was about half. National differences were also found when asking participants in an open-ended question what they thought sustainability meant. Figure 1 gives an overview of the top two categories of responses, per country. Country results for Sweden differed the most – this was due to the fact that the Swedish term Hållbarhet primarily refers to the longevity of food products themselves, e.g. shelf life, and only in its secondary meaning stands for what sustainability means in the English language.

Figure 1: Country differences in describing the term ‘sustainability’

.jpg)

“In your own words what do you think sustainability means?” (Top responses in each country; 4,408 respondents)

Focus group discussions in Germany, UK, France and Spain showed limited knowledge on the topic of ‘sustainability’. When participants were asked about a food and drink context, they quickly associated sustainability with healthiness and naturalness - appearing to see these issues as somewhat synonymous.

It can be summarised that study participants found the overall concept of sustainability difficult to engage with because it covers rather abstract issues without referring to anything specific directly.

What are people concerned about?

In general, study participants showed high concern with different sustainability-related issues. They also clearly indicated that they wanted to see more environmental and ethical labelling on food products (on average, 5.5 out of a 7-point scale, with 1=completely disagree to 7=completely agree).

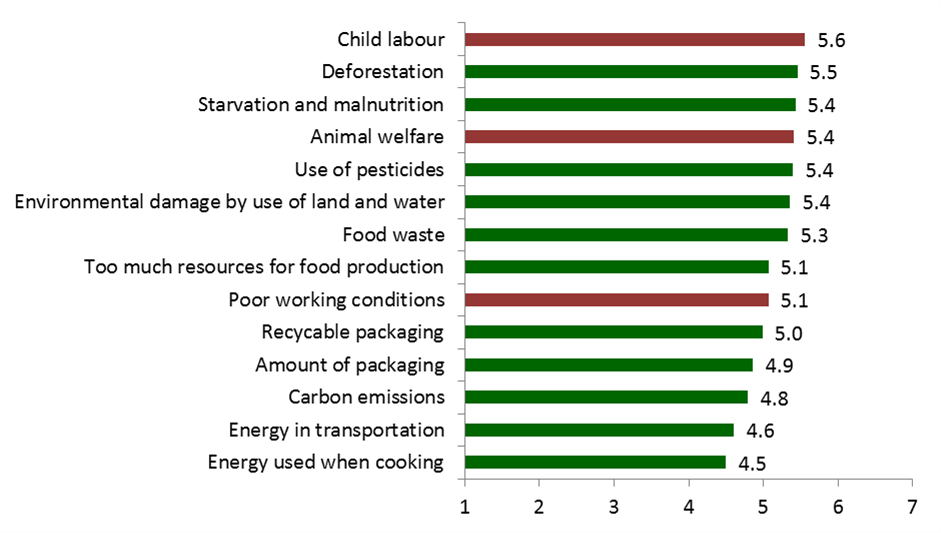

Figure 2: Levels of concern about sustainability-related issues

“How concerned are you personally about each of these issues?” (scale: 1=slightly concerned to 7=extremely concerned; 4,408 respondents)

In the focus groups, the topics animal welfare, the ‘naturalness’ of what is consumed, where food comes from (i.e. the country, the region, local producers) and Fairtrade were discussed the most. There was general support for initiatives that promote sustainability. However, only a few people were particularly engaged or informed and some key issues such as climate change were largely overlooked.

How familiar are consumers with sustainability labels?

The four sustainability labels selected for this study were Fairtrade, Animal Welfare, Rainforest Alliance and Carbon Trust. National adaptations were used where available.

Figure 3: Ethical and environmental labels used in the research

.jpg)

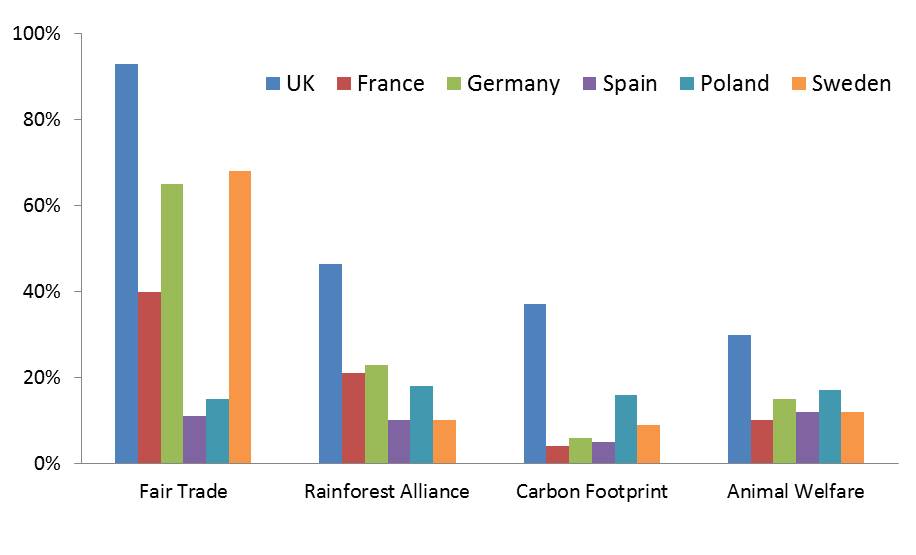

The idea of sustainability and social awareness labelling was generally well perceived throughout the study, as the labels address issues that people are concerned about. Responses to the survey showed that the majority of consumers would like to see specific labels used more often on food and drink products. The Fairtrade label was the most widely recognised of those tested, with around half of all respondents saying that they had seen it before. However, considerable differences were found across the six countries (Fig. 3). Spanish participants showed lowest familiarity with such labels, compared to participants from the UK who answered most often that they had seen each of the labels before.

Figure 4: Familiarity with sustainability labels

“Prior to this survey, had you seen this label before?” (% answering yes, 4,408 respondents)

When presenting the sustainability labels to the participants of the focus group discussions, the logos and the concept behind each were little known and understood, except Fairtrade. Participants also showed scepticism towards the validity of the labels and why manufacturers use them on their products.

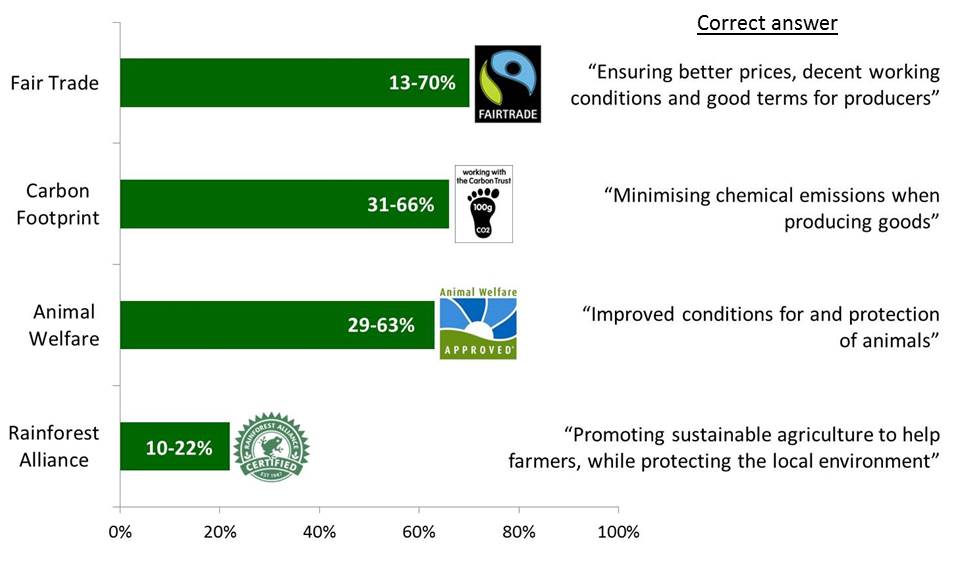

What do consumers think the labels mean?

When asked about the meaning of the four different sustainability labels, the majority of the respondents across the six countries marked the correct definitions for Fairtrade, Carbon Footprint and Animal Welfare. For the Rainforest Alliance logo, however, the majority opted for an incorrect answer (“Protecting wildlife in the rainforest”). Again, large differences in the number of correct answers could be found across the six countries. In line with results regarding the familiarity with these labels, respondents from the UK showed the highest understanding of the four labels. The least correct answers were given by Polish participants.

Figure 5: Sustainability labelling: percentage of correct answers across all 6 countries

“What do you think this label means?” (5 answering options plus “I don’t know”)

Additionally, study participants were shown the EU Eco-label which currently cannot be found on foods. The majority (75%) said they had not seen this label before. Of the 12% who said they had seen it, 20% incorrectly answered “on food and drink products” and 36% could not recall any product category they had seen it on. While close to half of all respondents (~45%) chose the correct definition, about a quarter opted for “I don’t know”.

What do people look for when they are shopping for food and drink?

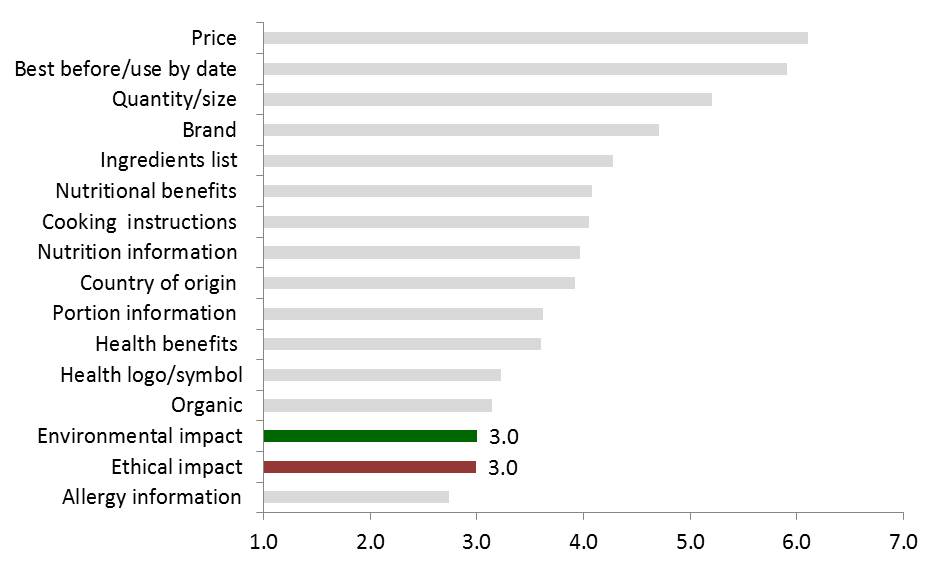

When asked what information consumers look for on food and drink packages, “environmental impact” and “ethical impact” were among the least selected sources of information. As shown in previous EUFIC studies, price and best before/use by date are most important when shopping food.1,2

Figure 6: Mean frequencies of looking for different information on packaging

“When buying food and drink products, how often do you look for the following information on the packaging?” (scale: 1=never to 7=always; 4,408 respondents)

Evidently, reasonably high concern about sustainability-related topics does not influence the type of information consumers look for most on food and drink products.

This finding was replicated in many of the focus group discussions where sustainability was considered a broader concept and not necessarily tied to the consumption context. In particular the German discussion participants showed a strong willingness to live ‘sustainable’ – however, a sustainable lifestyle was associated more with a general responsibility towards life, environment and future generations. Sustainability in the food and drink context was not top of mind.

How important is sustainability when choosing a product?

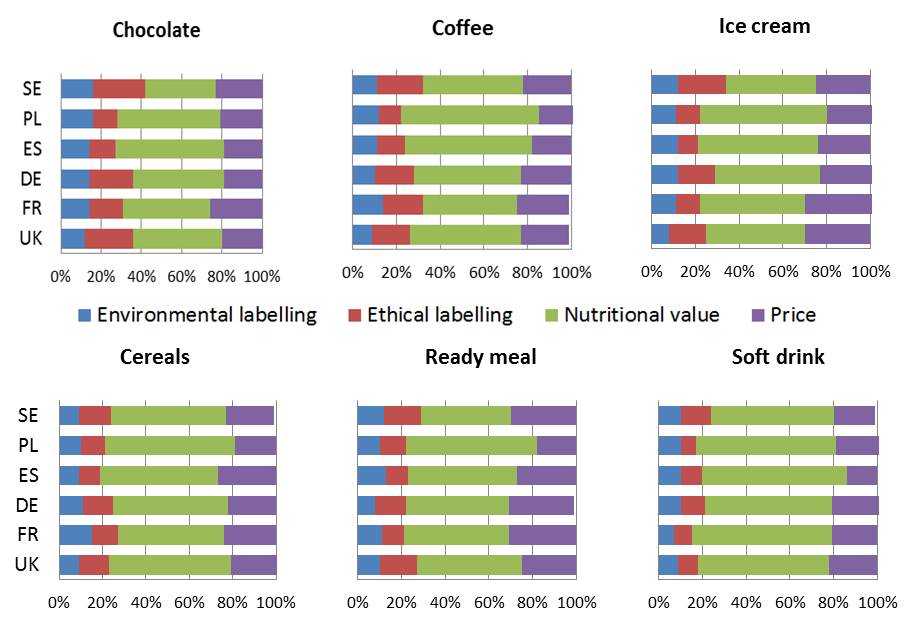

Study participants were asked to choose between different alternatives of food products from six different product categories: chocolate, coffee, ice cream, breakfast cereals, ready meals and soft drinks. Products within these categories varied in price and nutritional value as well as whether they had environmental and/or ethical labelling. By means of this choice task, results show clear differences in the relative importance of these different attributes: a high nutritional value was always the most important factor in choosing a product, followed by a low price. Although differences were evident for the different product categories and across the six countries, both environmental (Rainforest Alliance, Carbon Footprint) and ethical (Fairtrade, Animal Welfare) labels were least important in choosing a food product. Fig. 8 shows an overview on all countries, all products and the relative importance of all four product attributes.

Figure 7: Importance of price, nutritional value and environmental and ethical labelling across product categories and countries

The fact that the majority of people are concerned about sustainability issues but do not currently understand enough nor act upon it means that there is an appetite for more information, particularly in a food and drink context.

Participants in the focus group discussions who showed a strong interest in sustainability issues were especially favourable towards labels as they found them both convenient and reassuring. On the one hand, consumers prefer to fully understand which development food products undergo. On the other hand, a packaged product with a logo can serve to assure a certain quality/trust standard.

Where would people like to find this information?

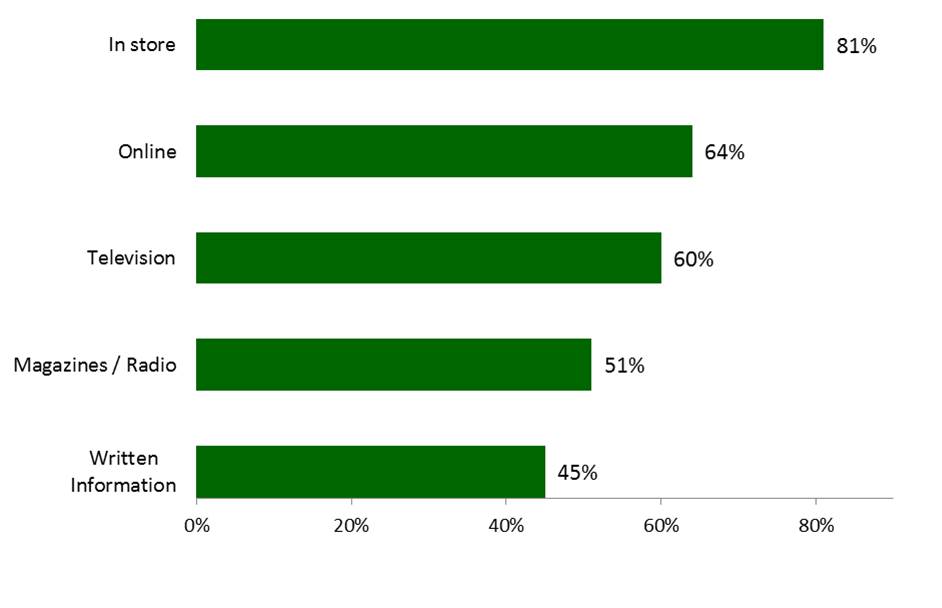

When asked where they would like to find more information on sustainability, respondents indicated in store (here: mainly labels on-pack) as their top choice, followed by online and TV (programmes, news and advertising).

Figure 8: Main sources of information in a sustainability context

"Where would you like to find more information about the sustainability aspects of food and drink products?”

How can sustainability influence food choice in the future?

Food and drink shopping is typically described as a routine, possibly under time pressure, and if special attention is paid, it is mostly centred on price.

Respondents in this study showed varying levels of checking information on food packaging. However, some recurring patterns included:

- women are far more likely to check information of any type

- for younger people it is all about price and other aspects are less important

- larger sub-groups of men and younger people say that they rarely or never check for environmental or ethical information

With levels of concern about sustainability-related issues generally high, and many focus group participants indicating that they would be interested in buying sustainable products, five key conditions have been identified in which sustainability could influence food choice:

- the individual already has an interest in sustainability issues;

- other key features such as price and quality are met;

- the label or information on the product is actually noticed;

- enough time in store to consider this information; and

- understanding what the label or other information means

Participants in the focus groups said that they would be more likely to notice and think about sustainability labels if they had better and trusted information about what the labels meant. While many participants were able to guess the right answer to the definition of the labels, they found it difficult to interpret the information in detail. It was argued that simpler labelling might help them better notice and engage with these issues.

Conclusions

The study has shown that people are familiar with and show concern about sustainability and social awareness issues. However, those factors do not translate into food choice (yet). Participants found the overall concept of sustainability abstract and difficult to grasp. Some individuals in the focus groups showed higher engagement with this topic, e.g., they favoured local and natural products in order to support regional production and ensure less transport (food miles).

Consumer awareness of sustainability is generally high but different groups show different levels of willingness or ability to put positive attitudes towards sustainability into practice. For example, levels of concern were consistent across education groups. Participants with a lower socio-economic status, however, seemed less equipped or able to act on these concerns compared to upper groups. In general, it was shown that concerns about sustainability increases with age and women seem more concerned than men.

Because of its complexity, the concept of sustainability itself is perhaps not the most effective way to communicate about related issues. Within the group discussions, few participants felt particularly confident talking about sustainability, and we measured a degree of misunderstanding in both parts of the research. More concrete issues such as animal welfare or child labour, however, were discussed in great detail and received both attention and willingness to engage, from participants.

It will be a task of education and communication to better tailor the messages and relate them to more specific rather than abstract concepts of sustainability. All actors in the food chain, including national authorities and consumer groups, need to engage with the consumer in communicating about sustainability, the meaning and consequences of this concept and how food and drink choice can contribute to ethical and environmental issues.

References

Market Research Agency: Ipsos MORI, UK

- EUFIC Forum n° 4 - Pan-European consumer research on in-store observation, understanding & use of nutrition information on food labels, combined with assessing nutrition knowledge.

- EUFIC Forum n° 5 - Consumer response to portion information on food and drink packaging: a pan-European study.

Quote as: EUFIC (2013). Sustainability and Social Awareness Labelling – a pan-European study on consumer attitudes, understanding and food choice. EUFIC Forum n° 6.