What happens when we reduce or stop eating meat? A micronutrient breakdown

Last Updated : 26 November 2025Key takeaways:

- Plant-based diets offer clear health and environmental benefits, including lower risks of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers, and a reduced ecological footprint compared to an omnivorous diet.

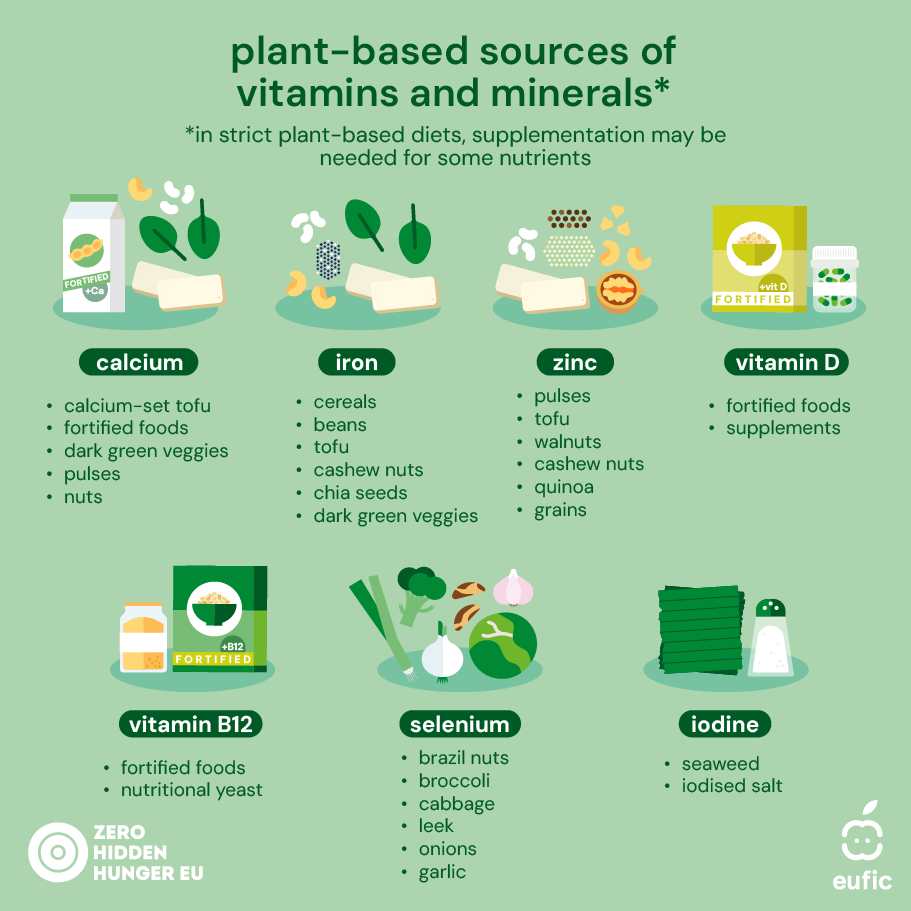

- Some nutrients require special attention when cutting back on meat, especially vitamin B12, iron, zinc, calcium, vitamin D, and omega-3s, because they’re less available or less absorbable from plant-based foods.

- Most minerals can be obtained from plant foods with good planning, but iron, zinc, calcium, and iodine may need strategies like food pairing (e.g., iron with sources of vitamin C), fortified foods (e.g., iodised salt), or improved preparation techniques (e.g., soaking, sprouting, fermenting, leavening) to enhance absorption.

- Vitamin B12 and often vitamin D require supplementation or fortified foods for individuals eating fully plant-based. Others, such as iron, zinc, calcium, and iodine, can generally be managed through a varied diet that includes fortified foods and techniques to enhance absorption.

Plant-based diets are no longer just a trend, they’re becoming a scientific and cultural spotlight. From flexitarians to vegans, more people are reducing meat consumption, drawn by promises of better health and a smaller environmental footprint. Studies consistently show these diets are linked to lower risks of chronic diseases, higher nutrient density, and a lighter ecological impact compared with traditional omnivorous diets1-2,4-6.

Yet, the question remains: are these diets nutritionally adequate for everyone? From children to older adults, understanding the micronutrient implications of cutting back on meat and animal products is crucial.

Switching to a plant-based diet: What are the benefits?

A plant-based diet does not have a single definition but generally refers to eating patterns that emphasise fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. While it can include vegan or vegetarian approaches, it more often means a plant-forward or flexitarian style of eating, where animal products are eaten in smaller amounts and most nutrients come from plant foods.

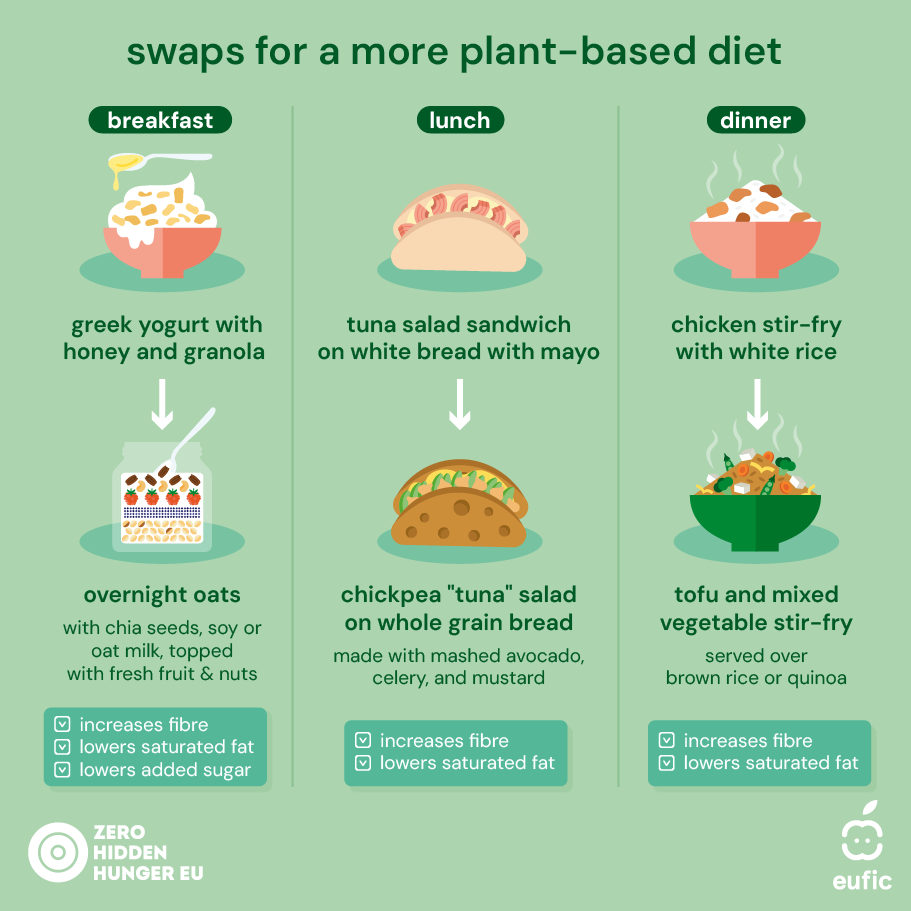

Diets rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds are linked to lower risks of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers8,9,13,14. They’re packed with fibre, antioxidants, and phytochemicals, while naturally lower in saturated fat, supporting heart health and weight management2,4,5.

The environmental benefits are equally compelling. Reducing animal products lowers greenhouse gas emissions, conserves water, and uses less land. In other words, going plant-forward isn’t just good for your body, it’s good for the planet.3

However, cutting out animal products changes your intake of key vitamins and minerals. Meat and dairy are top dietary sources of vitamin B12, iron, zinc, calcium, and vitamin D. Balanced plant-based diets can contain plenty of protein, magnesium, potassium, vitamin C, and fibre, but some nutrients need strategic planning or supplementation. This is especially the case for vitamin B12 and long-chain omega-3s, which are critical for nerve function and blood formation5,6,7. It’s also important to remember that certain nutrients, such as iron, zinc, and calcium, are often more bioavailable from animal sources than from plants, so you may need to consume higher amounts of plant foods or use preparation techniques that enhance absorption.

The following sections break down how to maintain optimal levels of iron, B12, zinc, vitamin D, and calcium when you reduce or remove meat.

Fig. 1 Plant-based sources of vitamins and minerals

How to get enough iron without eating meat

Iron is essential for oxygen transport and maintaining energy levels. While red meat is a good source of easily absorbed heme iron, plant-based diets rely on non-heme iron, which is absorbed less efficiently.

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anaemia, but people following a plant-based diet can maintain healthy iron levels by including iron-rich foods such as legumes, leafy greens, and fortified grains. Non-haem iron absorption can be boosted by pairing iron-rich foods with vitamin C sources like citrus, berries, or bell peppers. Population studies show that while vegetarians that meet their energy and nutrient needs are not at greater risk of iron deficiency, they may be at risk of lower ferritin levels (lower iron stores) so monitoring iron status is advisable11,16. Particular attention should be given to women of reproductive age and adolescents, as their physiological requirements for iron are increased, placing them at greater risk of inadequate intake.

Plant-based sources of iron include pulses such as lentils, chickpeas, and beans, as well as tofu, pumpkin seeds, quinoa, spinach, and fortified cereals. The bioavailability of non-haem iron from these foods can be enhanced through specific dietary practices, including consumption with vitamin C-rich foods, cooking in cast iron cookware, and maintaining variety in dietary sources.

Vitamin B12 and plant-based diets: Are you at risk of deficiency?

Vitamin B12 is a red flag nutrient when reducing animal foods. Essential for red blood cell formation, nervous system function, and DNA synthesis, vitamin B12 is virtually absent in unfortified plant foods.

Fortified plant-based drinks, fortified breakfast cereals, nutritional yeast, and supplements are important sources of vitamin B12 for those following plant-based diets. Monitoring intake is essential, as deficiency can lead to fatigue, neurological symptoms, and, in severe cases, nerve damage. Vegans and vegetarians are particularly at risk and may benefit from daily supplementation to maintain adequate levels11.

Vitamin B12 is not naturally found in plant foods, so those following a vegan diet need to rely on supplementation or fortified foods to meet their requirements and maintain optimal health.

Zinc absorption without meat: Challenges and plant-based fixes

Zinc is critical for immunity, wound healing, and cellular growth. Meat and shellfish are rich in bioavailable zinc, while plant foods contain phytates that can reduce absorption.

Plant-based sources of zinc include beans, lentils, hemp seeds, pumpkin seeds, sesame seeds, nuts, and whole grains. Absorption can be improved by soaking, sprouting, fermenting, or leavening these foods to reduce compounds that inhibit bioavailability. While vegetarians often meet overall zinc intake recommendations, slightly higher amounts may be beneficial due to reduced absorption efficiency. In some cases, particularly during pregnancy, adolescence, or for those following strict vegan diets, supplementation may be necessary to maintain adequate levels.

Optimising vitamin D intake without animal products

Vitamin D is essential for bone strength, immunity, and muscle function. Sunlight triggers the body’s natural production, but winter months or limited outdoor exposure often make dietary sources critical.11

Plant-based sources of vitamin D include fortified plant-based drinks, margarines, fortified breakfast cereals, and UV-exposed mushrooms. Despite these options, many public health guidelines recommend supplementation, particularly for vegans and individuals with limited sun exposure, to help maintain adequate vitamin D levels16.

Calcium absorption without dairy for plant-based diets

Calcium, keeps bones strong and muscles, nerves, and hearts functioning. While dairy is the traditional go-to, plant-based eaters can meet their needs through careful food choices. Good sources include tofu set with calcium, fortified plant drinks and yoghurts, tahini, almonds, and leafy greens such as kale and bok choy that are low in oxalates.11,16

It’s important to note that in high-oxalate greens, such as spinach, the bioavailability of calcium is much lower, and absorbed poorly by the body, making it a poor source of calcium. For most people, supplementation is unnecessary if fortified foods are consumed regularly.

How reducing animal products affects iodine intake

Iodine is a trace element required for production of thyroid hormones, which regulate metabolism, growth, and brain development, especially during pregnancy and early childhood. When someone cuts back on or eliminates animal products, their intake of iodine tends to drop, because many of the richest sources of iodine are seafood, fish, shellfish, eggs, milk and dairy. In Europe, dairy products are important sources of iodine in typical diets.

Plant-based foods generally have much lower, and more variable, iodine content depending on soil quality, use of iodine in farming practices, and whether products are fortified. Plant-based sources of iodine include iodised salt, fortified foods and seaweed. The iodine content of seaweed varies widely, and some types can contain very high levels that might cause adverse health effects. When consumed in moderate amounts, especially choosing lower-iodine varieties (for example some red or green seaweeds rather than brown kelp types), seaweeds can help meet iodine needs without exceeding safe limits.

It’s worth noting that availability of iodised salt varies by region and fortification of table salt is not mandatory in all EU countries. It’s important to check whether the salt you use is iodised if you rely on it as a source of iodine.17

Which vitamins and minerals need supplements?

While many nutrients can be obtained from plant foods with careful planning, some are difficult to get in adequate amounts without supplements. Vitamin B12 is the clearest example. It is virtually absent from unfortified plant foods, so supplementation or fortified products are essential for vegans. Vitamin D is also often recommended, especially in winter or for those with limited sun exposure. Others, such as iron, zinc, calcium, and iodine, can generally be managed through a varied diet that includes fortified foods and techniques to enhance absorption.

Figure 2. Plant-based swaps

Conclusion

Going plant-based can be a win-win for health and the planet but micronutrient planning is key. Nutrients such as vitamin B12, iron, zinc, calcium, vitamin D, and omega-3 fats need particular attention when animal products are reduced or removed. With careful food selection, fortified options, and targeted supplementation, plant-forward diets can meet nutritional needs, reduce overconsumed harmful nutrients such as saturated fat, and support global sustainability goals.

This article was produced in collaboration with Zero Hidden Hunger EU. Zero Hidden Hunger EU has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 101137127

References

- Plant-based diets and their impact on health, sustainability and the environment: a review of the evidence: WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2021. Licence: CC BY-

- Willett W, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393:447–492.

- Springmann M, et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature. 2018;562:519–525.

- Pinheiro, C., Silva, F., Rocha, I., Martins, C., Giesteira, L., Dias, B., Lucas, A., Alexandre, A.M., Ferreira, C., Viegas, B., Bracchi, I., Guimarães, J., Amaro, J., Amaral, T.F., Dias, C.C., Oliveira, A., Ndrio, A., Guimarães, J.T., Leite, J.C. & Negr

- Key, T.J.; Papier, K.; Tong, T.Y.N. Plant-based diets and long-term health: Findings from the EPIC-Oxford study. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 190–198.

- Wang, T.; Masedunskas, A.; Willett, W.C.; Fontana, L. Vegetarian and vegan diets: Benefits and drawbacks. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3423–3439.

- Neufingerl, N.; Eilander, A. Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters:A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 14, 29.

- Satija A, Hu FB. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28(7):437–441.

- Hemler EC, Hu FB. Plant-based diets for cardiovascular disease prevention: all plant foods are not created equal. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2019;21:18.

- Afshin A, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2019;393:1958–1972.

- Raj, S., Guest, N.S., Landry, M.J., Mangels, A.R., Pawlak, R. & Rozga, M., 2025. Vegetarian dietary patterns for adults: A position paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 125(6), pp.831-846.e

- Hu FB. Plant-based foods and prevention of cardiovascular disease: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:544S–551S.

- Micha R, et al. Association between dietary factors and mortality from heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2017;317(9):912–924.

- Micha R, et al. Global, regional, and national consumption of major foods and nutrients in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:186–197.

- Satija A, et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002039.

- Bakaloudi, D.R., et al, 2021. Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet: A systematic review of the evidence. Clinical Nutrition, 40(5),

- Bath SC, et al. 2022. A systematic review of iodine intake in children, adults, and pregnant women in Europe – comparison against dietary recommendations and evaluation of dietary iodine sources. Nutrition Reviews, 80(11):2154-2177.