Acrylamide in food: What it is & How to reduce levels

Last Updated : 26 November 2025Key takeaways:

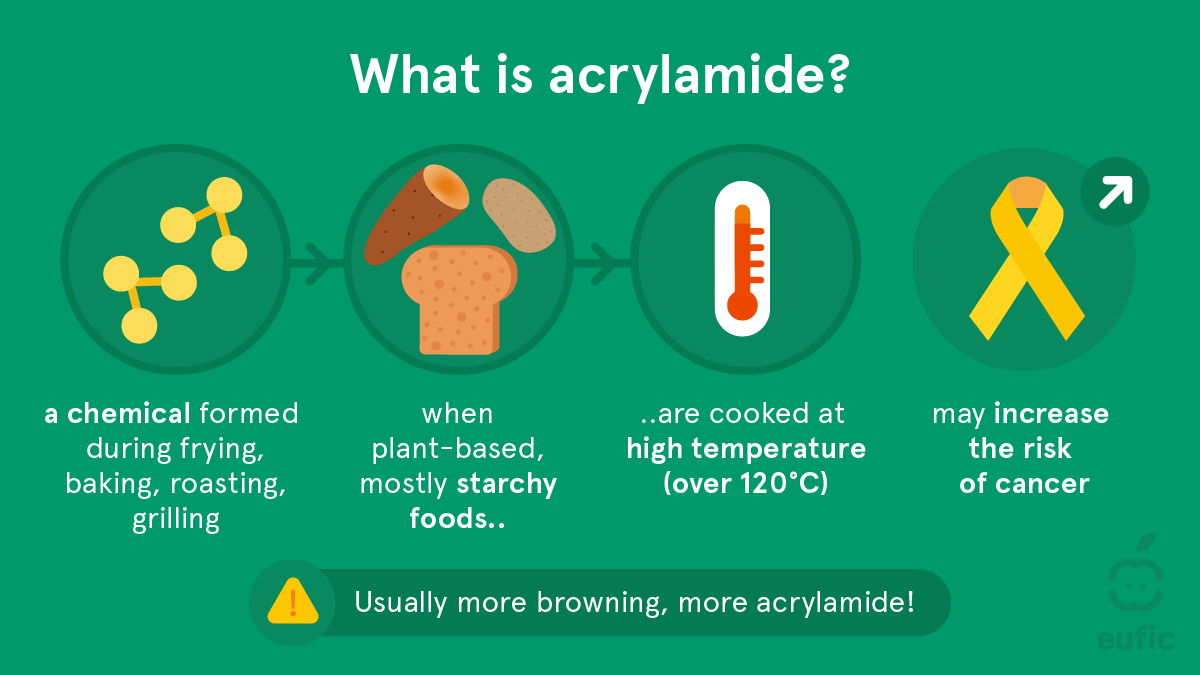

- Acrylamide forms naturally in starchy foods cooked at high temperatures, such as frying, baking, roasting, and toasting, and is produced when certain sugars react with the amino acid asparagine during the Maillard browning reaction.

- High levels of acrylamide can cause cancer in animals, and while human evidence is not conclusive, health agencies recommend reducing dietary exposure where possible as a precaution.

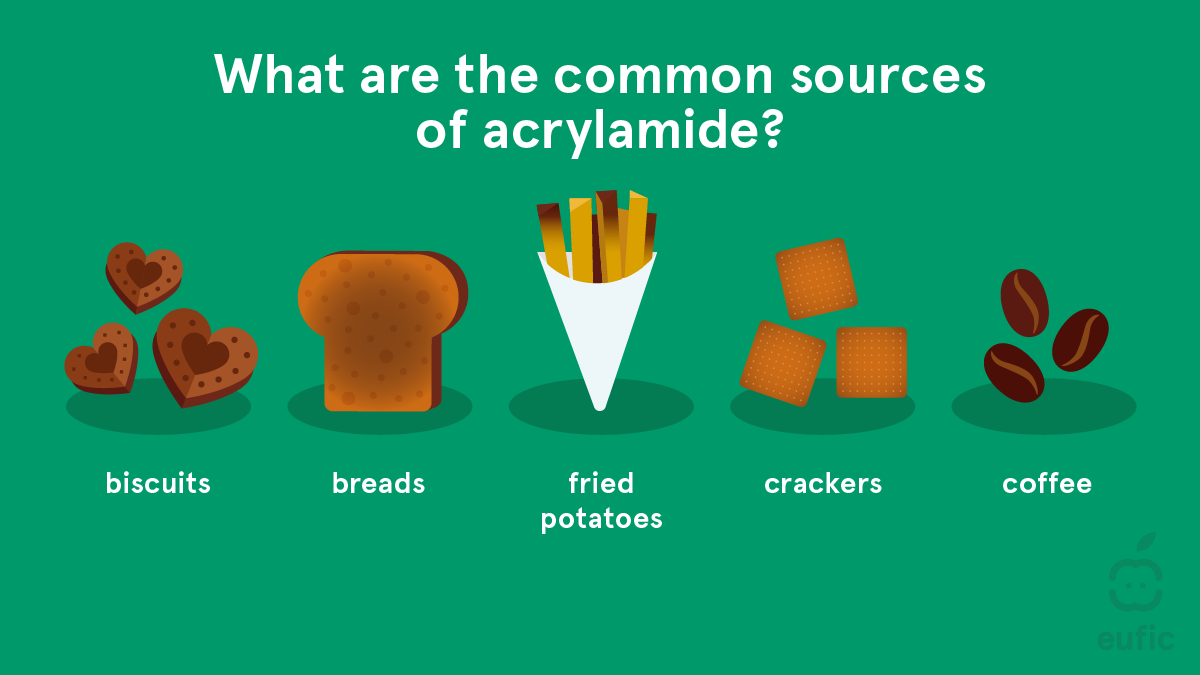

- Common dietary sources of acrylamide include biscuits, bread and baked goods, fried potatoes (e.g., potato chips, French fries), crackers, and coffee. Cigarette smoke also contain acrylamide.

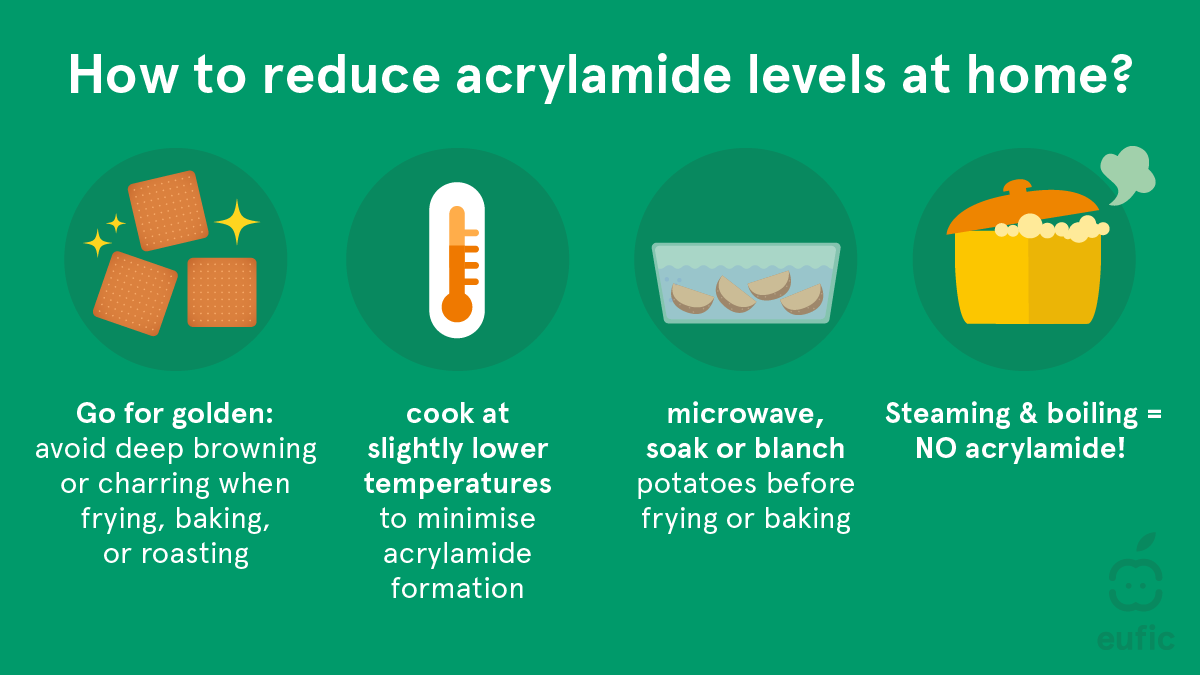

- Acrylamide exposure can be reduced at home by avoiding over-browning and charring, using lower cooking temperatures, soaking or blanching potatoes before frying or baking, and choosing steaming or boiling over frying or roasting.

- The EU requires food businesses to apply mitigation measures and meet benchmark levels to keep acrylamide as low as reasonably achievable. This has contributed to major reductions in products like potato crisps.

Acrylamide is a chemical that forms when starchy foods like bread, biscuits, and potatoes, are cooked at high temperatures through frying, baking, roasting, or toasting. It develops as part of the natural browning process that gives foods their appealing colour and flavour. However, studies have shown that high levels of acrylamide can cause cancer in animals. Although the link between acrylamide and cancer in humans is not yet conclusive, it is advisable to take precautions by reducing dietary exposure.

To help minimize acrylamide levels in food, the European Union has implemented regulations for the food industry. But food safety isn't just about what happens in factories, it also starts in our own kitchens. At home, we can reduce acrylamide formation by avoiding excessive browning, soaking or blanching potatoes before frying, and choosing cooking methods that use lower temperatures.

This article explains what acrylamide is, how it forms, its potential link to cancer, which foods contain it, and practical tips for reducing intake. It also explore how emerging cooking methods, such as air fryers, compare to traditional ovens in acrylamide formation.

What is acrylamide?

Acrylamide is a compound that forms in many foods when they are cooked at high-temperatures. First discovered in food in 2002, acrylamide is produced when certain sugars react with an amino acid called asparagine. This process, known as the Maillard reaction, occurs when foods are heated above approximately 120°C.1

The Maillard reaction is what gives many foods their delicious flavour and golden-brown colour. However, it also leads to the unintentional formation of acrylamide. Although this compound is not deliberately added to food, it naturally develops during common cooking methods such as frying, roasting, or baking, all of which involve high temperatures.

Acrylamide and cancer

Laboratory studies have shown that high doses of acrylamide can cause cancer and affect reproduction in animals. Based on these findings, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified acrylamide as a Group 2A probable carcinogen.2 This classification means that while the link between acrylamide and cancer in humans remains uncertain, studies in animal provide enough evidence to suggest it likely has carcinogenic potential.

The main concern is that acrylamide and its metabolite, glycidamide, can damage DNA, potentially contributing to cancer development over a lifetime of exposure. As a precaution, public health authorities and regulatory bodies encourage efforts to lower acrylamide levels in food, and experts recommend reducing dietary exposure where possible.3,4

Foods high in acrylamide

The amount of acrylamide in a food depends on several factors, including the type of food, its natural content of asparagine and sugars, and how it is cooked. Below are some common food categories that tend to contain higher acrylamide levels.

Fried foods (e.g. potato chips, French fries)

Fried potato products are among the most well-known sources of acrylamide. Potatoes naturally contain high levels of asparagine and sugars, which, when exposed to the intense heat of deep-frying, accelerate the Maillard reaction, resulting in higher acrylamide formation.5 A simple way to reduce acrylamide levels is to soak potato slices in water before frying as this helps remove some of the free sugars that contribute to its formation.

Coffee

Coffee is one of the most popular beverages worldwide and a notable source of acrylamide. The compound forms during the roasting process, which typically happens at temperatures above 200 °C. Initially, as roasting time and temperature increase, acrylamide levels rise. However, after certain point, they begin to decline as asparagine, one of the key precursors, is depleted, and acrylamide starts to break down. The type of coffee bean also plays a role: Robusta beans generally contain slightly more acrylamide than Arabica beans due to their naturally higher asparagine content.5,6

Bread and baked goods

Baked goods, particularly bread crusts, are another source of acrylamide. When bread is baked, the high temperatures that create a golden crust also contribute to acrylamide formation. Darker, well-toasted bread generally contains higher levels of acrylamide than lighter-coloured bread. Additionally, the type of flour and the recipe, especially the presence of added sugars, can influence acrylamide levels.

Did you know? Acrylamide is not the same as the black, charred parts of burnt food. It actually forms during the early stages of browning, long before food becomes completely burnt.

Dried fruits (e.g. prunes)

Dried fruits, such as prunes, can also contain acrylamide, though usually in smaller amounts than fried or roasted starchy foods. During the drying process, particularly when high temperatures are used, natural sugars in the fruit can react with amino acids to form acrylamide. Although the levels are generally low, dried fruits are consumed regularly, which means they can still contribute to overall dietary exposure.

Other foods

Acrylamide can also be found in other foods like breakfast cereals and biscuits. The amount varies depending on the ingredients, processing conditions, and cooking methods, meaning that even similar foods can have different levels. In general, foods that are baked, toasted, or fried at high temperatures under low-moisture conditions tend to have more acrylamide than those that are boiled or steamed. Roasted nuts can also contain acrylamide, though usually in lower amount than starchy foods like potatoes.

|

FOOD ITEM |

MEDIAN ACRYLAMIDE LEVEL (µg/kg)ª |

EU BENCHMARK LEVEL (µg/kg)* |

|

Bakery Products |

||

|

Wheat-based soft bread |

15 |

50 |

|

Other breads |

25 |

100 |

|

Biscuits and wafers |

103 |

350 |

|

Crackers |

183 |

400 |

|

Coffee Products |

||

|

Roasted coffee |

203 |

400 |

|

Instant coffee |

620 |

850 |

|

Potato Products |

||

|

French fries |

196 |

500 |

|

Potato crisps and snacks |

389 |

750 |

|

Other Products |

||

|

Breakfast cereals (bran/whole grain) |

135 |

300 |

|

Breakfast cereals (wheat/rye, non-bran based) |

140 |

300 |

|

Breakfast cereals (maize, oat, spelt, barley, rice) |

50 |

150 |

|

Cereal-based baby foods |

15 |

40 |

|

Roasted nuts and fruits |

25 |

– |

Table 1: Acrylamide median levels in common foods. Note: µg/kg = micrograms per kilogram. Source: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/a...

ªThe median is the middle value in a set of measurements, meaning half the samples have higher levels and half have lower.

*EU benchmark levels, set by Regulation 2017/2158, are guidelines to help reduce acrylamide in food. They are not legal limits but suggest safe levels for food businesses to follow.

Smoking and acrylamide

Studies show that cigarette smoke contains acrylamide, and smokers tend to have three to five times higher levels of this compound in their bodies compared to non-smokers.7 This means that, in addition to acrylamide from food, smoking can significantly increase overall exposure, potentially raising the associated risks.

How to reduce acrylamide levels when cooking ?

Reducing acrylamide in your diet begins with a few simple changes in how you store, prepare and cook food at home. Since acrylamide forms when starchy foods are cooked at high temperatures through the Maillard reaction, avoiding overcooking is key. Foods that are excessively browned or charred contain much more acrylamide, so aim for a light golden colour rather than a deep brown. In addition, using slightly lower cooking temperatures, even if it takes a little longer, can also help reduce acrylamide formation.5

Pre-treating foods before cooking can also be key. For example, soaking raw potato slices in water for about 30 minutes helps remove sugars that react with asparagine to form acrylamide. Similarly, blanching (briefly boiling potatoes before frying or baking) also lowers acrylamide levels by reducing free asparagine and sugars. Another effective method is microwaving starchy foods like potatoes before frying or baking, which has been shown to reduce acrylamide formation by up to 40%.8

Choosing the right cooking method can also help. Steaming and boiling do not produce acrylamide at all, making them great alternatives to frying or baking. If you bake frequently using rice flour instead of wheat flour can also lower acrylamide levels in baked goods, since rice flour naturally contains less free asparagine.9

There is ongoing debate about whether air fryers are better than conventional ovens for reducing acrylamide. Air fryers use hot air to create a crispy texture with less oil than deep frying but studies suggest they may produce similar or even higher acrylamide levels compared to oven cooking. This is because air fryers still expose food to high temperatures and may create "hot spots" that lead to over-browning. Ovens, on the other hand, distribute heat more evenly. Regardless of the appliance you use, keeping an eye on the food’s colour and avoiding overcooking is key to minimizing acrylamide formation. 9,10

European union legislation and its impact

To address concerns about acrylamide in food, the European Union has taken proactive steps to reduce its levels in the food supply. In November 2017, the European Commission adopted Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158, which sets mandatory mitigation measures and benchmark levels for acrylamide in foods like potato products, cereal-based foods, and coffee. Food business must follow these measures as part of their safety management systems, applying “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) principle to minimize acrylamide formation.5

Under this framework, companies are required to regularly test their products to ensure acrylamide levels stay within the established benchmarks. In addition, the EU has issued Commission Recommendation (EU) 2019/1888, encouraging further monitoring of acrylamide in foods not fully covered by the regulation.10

The implementation of these regulatory measures has helped lower acrylamide levels in many food products, making the food supply safer. For example, a European study found that average acrylamide levels in potato crisps dropped by more than half from levels observed in 2002 to a record low in 2018 and the proportion of products exceeding safety benchmarks fell from over 40% in 2002 to less than 8% in 2019.11 These improvements help ensure that the food you buy at supermarkets and enjoy in restaurants is safer, and they provide reassurance that both industry practices and regulatory standards are working to protect public health.

What are food manufacturers doing to reduce acrylamide in their products?

Food manufacturers are using innovative techniques to minimise acrylamide levels while maintaining product quality and taste. Advanced processing methods, such as pulsed electric field (PEF) and ultrasound treatments, help remove reactive components from food before high-temperature cooking. These nonthermal or hybrid technologies allow for safer food production without compromising flavour or texture.

Additionally, manufacturers are modifying recipes to lower asparagine levels or reducing sugar content, both of which contribute to acrylamide formation. This includes using alternative raw materials or adjusting cooking temperatures and times to find the right balance between flavour and food safety. In bakery products, for example, companies may reduce added sugars or choose flours with lower free asparagine content to naturally decrease acrylamide levels.5,12,13

Summary

Acrylamide is a naturally occurring compound formed when certain foods are cooked at high-temperatures. It can be found in a variety of everyday items, including potato chips, French fries, toasted bread, and roasted coffee. While studies in human have not definitively linked dietary acrylamide to cancer, public health recommendations and evolving regulations emphasize the importance of reducing exposure as a precaution.

Consumers can take simple steps to lower their acrylamide intake without sacrificing flavour. Avoiding excessive browning, pre-soaking or blanching starchy vegetables and choosing lower-temperature cooking methods can all help. Following cooking instructions on packaged foods is another easy way to minimize acrylamide formation.

With ongoing research and innovation in food processing, the combined efforts of regulators, food manufacturers, and consumers are leading the way toward safer food practices.

The scientific content of this article was reviewed by ACRYRED (COST Action CA21149, Reducing Acrylamide Exposure of Consumers by a Cereals Supply-chain Approach Targeting Asparagine).

References

- Tareke E, Rydberg P, Karlsson P, Eriksson S & Törnqvist M (2002). Analysis of acrylamide, a carcinogen formed in heated foodstuffs. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 50(17):4998-5006. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jf020302f.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1994). Some Industrial Chemicals. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507457/.

- FDA (2024). Acrylamide in Food. https://www.fda.gov/food/process-contaminants-food/acrylamide. Accessed 27 March 2025.

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) (2015). Scientific opinion on acrylamide in food. EFSA Journal 13(6):4104. https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4104.

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158 (2017). Mitigation measures and benchmark levels for the reduction of the presence of acrylamide in food. Official Journal of the European Union. https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/chemical-safety/contaminants/cat

- Aktağ IG, Hamzalıoğlu A, Kocadağlı T & Gökmen V (2022). Dietary exposure to acrylamide: A critical appraisal on the conversion of disregarded intermediates into acrylamide and possible reactions during digestion. Current Research in Food Science 5:1118-

- Kenwood BM, Zhu W, Zhang L, et al. (2022). Cigarette smoking is associated with acrylamide exposure among the U.S. population: NHANES 2011–2016. Environmental Research 209:112774. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35074357/.

- Abhigna S, Kulkarni M, Khandalkar N & Patil AV (2024). Acrylamide in Food: From Formation to Regulation and Emerging Solutions for Safer Consumption. FoodSci: Indian Journal of Research in Food Science and Nutrition 69-77. https://www.opensciencepublica

- Chen Y, Wu Y, Fu J & Fan Q (2020). Comparison of different rice flour- and wheat flour-based butter cookies for acrylamide formation. Journal of Cereal Science 95:103086. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S073352102030477X.

- European Commission (2019). Commission Recommendation (EU) 2019/1888 on the monitoring of the presence of acrylamide in certain foods. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2019/1888/oj/eng. Accessed 27 March 2025.

- Powers SJ, Mottram DS, Curtis A & Halford NG (2021). Progress on reducing acrylamide levels in potato crisps in Europe, 2002 to 2019. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A 38(5):782-806. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19440049.2020.187108

- Pandiselvam R, Süfer Ö, Özaslan ZT, et al. (2024). Acrylamide in food products: Formation, technological strategies for mitigation, and future outlook. Food Frontiers 5:1063-1095. https://doi.org/10.1002/fft2.368.

- Sarion C, Codină GG & Dabija A (2021). Acrylamide in bakery products: A review on health risks, legal regulations and strategies to reduce its formation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(8):4332. https://doi.org/10.3