Microalghe: cosa sono, come si coltivano e si usano

Ultima modifica : 02 February 2023Algae come in many shapes and sizes, and although most of us know only a few species, there are many others that are becoming increasingly important organisms for our future. Microalgae, in particular, have such great potential that they deserve to appear much more on our plates – as part of a healthy and sustainable diet. This article describes what microalgae are, presents some edible species of microalgae, and explains why we might want to consume more and more of them.

What are microalgae and what are the most common types?

Algae species are classified into two categories: macroalgae, such as seaweed, and microalgae.

Microalgae consist of a single cell or a small number of cells gathered into a very simple structure, which can grow rapidly and multiply into a large nutrient-rich biomass.

You may have heard of Chlorella and Spirulina. Both are species of microalgae. These blue-green species are among the oldest species of life on the planet. Chlorella is native to Taiwan and Japan, while Spirulina is found in Africa and Asia.

Not only are they both safe to eat, but they are also associated with numerous health benefits.

In addition to Chlorella and Spirulina, there are more than fifty thousand different types of microalgae species. 1 They are all abundant in nature and are found in both fresh and salt water, such as lakes, rivers and seas. They can grow in many different environments and tolerate a wide range of temperatures and conditions, from salty Dead Sea2 to the Arctic and Antarctic. 3

Should microalgae be included in a healthy diet?

Macroalgae are already commonly consumed in many parts of the world. Seaweed, for example, has been a key ingredient in Asian cuisine for thousands of years, particularly in Japan, Korea and China. They are rich in nutrients and regular consumption contributes to heart health,4 gut health5 and a healthy immune system. 6

One of the most popular algae is Nori seaweed, which is used in sushi. Nori seaweed is also a rich source of iodine, a key nutrient in the production of our thyroid hormones that affect our overall metabolism. However, some species of macroalgae, such as laminares, which are one of the largest algae species,7 may contain high levels of algae. Excessive amounts of iodine can increase the risk of negative health effects associated with our thyroid.

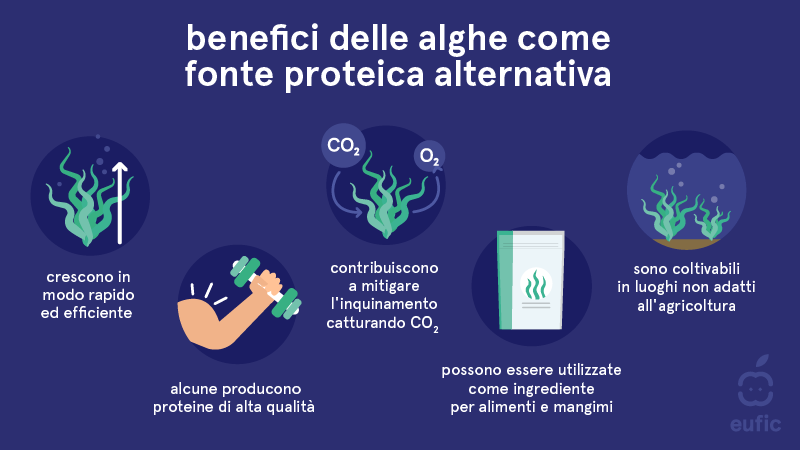

Microalgae may be less prevalent as food, but those that have been deemed safe to eat are becoming strong contenders in the race to find sustainable, nutritious protein alternatives to feed our growing global population. It is a more environmentally friendly alternative to animal protein, as they require much less land and fresh water for production than animal protein. 8 They are also a rich source of vitamin A, B, C and B12. Microalgae also contain iodine, but less than macroalgae. 9

Some species can give a protein supply to common foods, such as Spirulina, which can be added to bread dough10 to creams of plant origin, as shown here by the ProFuture project. 11th

In addition to offering sustainable sources ofprotein 12 and fiber, microalgae are also a source of healthy fats, including omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Omega 3 and 6 are essential fatty acids, which means that the human body cannot produce them on its own. Therefore, our intake must take place through nutrition. Although fish can be a source of essential fatty acids, due to rising prices and growing concerns about its sustainability, microalgae are seen as a potential alternative source to meet these nutritional needs.

Come possiamo aumentare il consumo di microalghe in Europa?

Attualmente, infatti, solo 10 specie di microalghe sono autorizzate al consumo alimentare in Europa.13 In Europa, l'Autorità europea per la sicurezza alimentare deve valutare la sicurezza di qualsiasi nuovo alimento prima che possa essere prodotto o venduto ai consumatori, e questo è un processo lungo e costoso.

Per la maggior parte degli europei, le microalghe sono ancora un alimento insolito. L'aggiunta di microalghe agli alimenti conosciuti e lo studio delle reazioni dei consumatori nei loro confronti sono passi cruciali per garantire che i nuovi prodotti possano entrare nei nostri mercati.

Per cos'altro possono essere utilizzate le microalghe?

Con i combustibili fossili che causano il rapido deterioramento degli habitat naturali, il riscaldamento globale e i problemi sanitari in tutto il mondo, vi è una crescente domanda di fonti energetiche rinnovabili.

Le microalghe sono sempre più utilizzate come biocarburante, un'alternativa rinnovabile e sostenibile al combustibile fossile che14 è accessibile a livello locale.

Le microalghe possono trasformare in modo efficiente l'energia solare in biomassa e sono ottime nel catturare l'anidride carbonica dall'atmosfera15 per contribuire a ridurre le emissioni di carbonio. E poiché la stragrande maggioranza delle specie non è commestibile, l'uso delle microalghe per produrre biocarburanti non sottrae nulla alla catena alimentare umana o animale.

Le microalghe vengono utilizzate oltre al cibo e all'energia, per esempio, nei cosmetici, nei farmaci e nei biofertilizzanti.

Come crescono le microalghe?

Le microalghe sono molto adattabili e possono essere coltivate in molti ambienti differenti. Mentre alcune specie possono crescere in Islanda, altre prosperano in un clima desertico. Possono crescere in grandi biomasse ricche di nutrienti che aiutano a sostenere altre vite intorno a loro. Forniscono infatti il 75% dell'offerta globale di ossigeno.16

Le microalghe generalmente riescono bene a trasformare l'anidride carbonica, i nutrienti e l'acqua in proteine, grassi e carboidrati attraverso la fotosintesi. E possono riprodursi rapidamente; non hanno fusti, radici o foglie – che richiedono molta energia per la loro crescita – quindi possono utilizzare l'anidride carbonica e i nutrienti in modo più efficiente rispetto alle piante terrestri.17

Poiché le microalghe crescono più rapidamente delle colture e del bestiame, possono produrre più proteine utilizzando meno tempo e risorse e utilizzando meno terra. Le microalghe possono produrre tra le quattro e le 15 tonnellate di proteine per ettaro all'anno, rispetto al range tra 0,6 e 1,2 della soia.18

Questo le rende risorse ottime per l'agricoltura industriale.

Come si possono coltivare le microalghe?

La coltivazione industriale di microalghe per la produzione di biocarburanti e bioprodotti19 è cresciuta notevolmente negli ultimi anni, e lo fa in svariati modi poiché diverse alghe richiedono condizioni diverse. Mentre la Spirulina e la Clorella richiedono acqua dolce, la specie di microalghe Tetraselmis20 può crescere solo in acqua salata.

Un metodo prevede l'uso di un fotobioreattore. Durante questo processo, le cellule delle specie di microalghe vengono coltivate in piccoli palloncini di vetro contenenti acqua e nutrienti che consentono loro di riprodursi e vengono anche alimentate con anidride carbonica e luce.

Le cellule vengono poi trasferite all'aperto ed esposte alla luce solare, e poi in un fotobioreattore tubolare, dove ricevono più luce solare e più sostanze nutritive prima di essere raccolte.

La produzione di microalghe è ancora agli inizi. Aumentare il processo al punto da poter soddisfare la domanda di cibo comporta diverse sfide.21 Ad esempio, la produzione richiede molte risorse, tra cui l'enorme costo dell'automazione per rendere tutto il processo più efficiente.

La buona notizia è che numerosi governi e aziende stanno cercando di ridurre i costi operativi per contribuire a rendere la produzione di microalghe redditizia dal punto di vista commerciale.22

Conclusione

Le microalghe stanno contribuendo a rispondere ad alcuni dei problemi più urgenti del mondo moderno, come nutrire una popolazione in crescita e trovare alternative sostenibili ai combustibili fossili. E, con più investimenti ed interesse, possono apportare un grande contributo.

Anche se questi problemi grandi e complessi possono apparire alla maggior parte delle persone come un mondo lontano, ci sono molti modi per introdurre le alghe nella nostra vita, che sia con il pane potenziato alla Spirulina, o con una porzione abbondante di sushi.

Questo articolo è stato prodotto in collaborazione con ProFuture. ProFuture ha ricevuto un finanziamento dal programma di ricerca e innovazione Horizon 2020 dell'Unione europea, nell'ambito dell'accordo di sovvenzione n. 862980.

Questo articolo è stato prodotto in collaborazione con ProFuture. ProFuture ha ricevuto un finanziamento dal programma di ricerca e innovazione Horizon 2020 dell'Unione europea, nell'ambito dell'accordo di sovvenzione n. 862980.

Riferimenti

- Elisabeth, B., Rayen, F., & Behnam, T. (2021). Microalgae culture quality indicators: a review. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 41(4), 457-473.

- Oren, A., Ionescu, D., Hindiyeh, M., & Malkawi, H. (2008). Microalgae and cyanobacteria of the Dead Sea and its surrounding springs. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, 56(1-2), 1-13.

- Mock, T., & Thomas, D. N. (2008). Microalgae in polar regions: linking functional genomics and physiology with environmental conditions. In Psychrophiles: from biodiversity to biotechnology (pp. 285-312). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Fitzgerald, C., Gallagher, E., Tasdemir, D., & Hayes, M. (2011). Heart health peptides from macroalgae and their potential use in functional foods. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 59(13), 6829-6836.

- Chen, L., Xu, W., Chen, D., Chen, G., Liu, J., Zeng, X., ... & Zhu, H. (2018). Digestibility of sulfated polysaccharide from the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum and its effect on the human gut microbiota in vitro. International Journal of Biological Macr

- Fazekas, T., Eickhoff, P., Pruckner, N., Vollnhofer, G., Fischmeister, G., Diakos, C., ... & Lion, T. (2012). Lessons learned from a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study with a iota-carrageenan nasal spray as medical device in children with acu

- Peter P.A. Smyth (2021) Iodine, Seaweed, and the Thyroid. European Thyroid Journal, 10(2): 101–108

- Martín P. Caporgno, Alexander Mathys (2018), Trends in Microalgae Incorporation Into Innovative Food Products With Potential Health Benefits, Frontiers in Nutrition, 5: 58.

- Inger Aakre, Dina Doblaug Solli, Maria Wik Markhus, Hanne K. Mæhre, Lisbeth Dahl, Sigrun Henjum, Jan Alexander, Patrick-Andre Korneliussen, Lise Madsen, and Marian Kjellevold (2021), Commercially available kelp and seaweed products – valuable iodine sourc

- ProFuture. (2020). Bread with a marine twist – using Spirulina to enrich bakery products.

- ProFuture. (2021). More foods going green at IRTA – adding microalgae to vegetable creams, crackers & grissini.

- Andrade, L. M., Andrade, C. J., Dias, M., Nascimento, C., & Mendes, M. A. (2018). Chlorella and spirulina microalgae as sources of functional foods. Nutraceuticals, and Food Supplements, 6(1), 45-58.

- Pierre, Guillaume, et al. "What is in store for EPS microalgae in the next decade?." Molecules 24.23 (2019): 4296.

- Khan, M. I., Shin, J. H., & Kim, J. D. (2018). The promising future of microalgae: current status, challenges, and optimization of a sustainable and renewable industry for biofuels, feed, and other products. Microbial cell factories, 17(1), 1-21.

- Sayre, R. (2010). Microalgae: the potential for carbon capture. Bioscience, 60(9), 722-727.

- ProFuture. (2019). Website About section.

- Microalgae is nature’s ‘green gold’: our pioneering project to feed the world more sustainably, (2022), Carole Anne Llewellyn

- Koyande, A. K., Chew, K. W., Rambabu, K., Tao, Y., Chu, D. T., & Show, P. L. (2019). Microalgae: A potential alternative to health supplementation for humans. Food Science and Human Wellness, 8(1), 16-24.

- Khan, M. I., Shin, J. H., & Kim, J. D. (2018). The promising future of microalgae: current status, challenges, and optimization of a sustainable and renewable industry for biofuels, feed, and other products. Microbial cell factories, 17(1), 1-21.

- ProFuture. (2020). Behind the scenes of microalgae production.

- Hannon, M., Gimpel, J., Tran, M., Rasala, B., & Mayfield, S. (2010). Biofuels from algae: challenges and potential. Biofuels, 1(5), 763-784.

- Qari, H., Rehan, M., & Nizami, A. S. (2017). Key issues in microalgae biofuels: a short review. Energy Procedia, 142, 898-903.